A Cry for Help: Pakistan’s Broken Education System

The saying “If you think education is expensive, try ignorance”, attributed to Derek Bok – the former president of Harvard University, holds a plethora of resonance for a developing country like Pakistan. Compared to the global standard of spending 4% of GDP on education, Pakistan only spends around 2.3% of its GDP on education, which happens to be the lowest in the South-Asian region. The inadequate spending on schools stems from the government’s nonchalant attitude and general disinterest in the education sector. Because of this, Pakistan’s budget allocation for education is far less than what is advised by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

The 2019 Annual Status of Education Report shows the overall literacy rate in the country to be 60%, with 71% male literacy rate compared to 49% female literacy. Despite these statistics showing an improvement from the past trends, the Human Development Report of 2019 remained unfazed. According to the findings of the report, Pakistan failed to show significant improvements in key educational indicators concerned with the rate of literacy, overall enrolment ratio, and education related expenditure. In the same year, Pakistan was also ranked 152nd out of 189 countries on the Human Development Index (HDI) under the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Comparing Pakistan’s Education sector to other developing countries in the region further paints a dismal picture, as Pakistan lingers behind it its quest in providing quality education. Pakistan suffers from the third-highest primary school dropout rates in the region, estimating at 23%, only behind countries such as Bangladesh and Nepal. In a 2016 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report titled “Education for People and Planet: Creating Sustainable Futures for All”, it was found that Pakistan is 50 years behind in achieving its primary education goals, while adding another 10 years in its path to achieving its secondary education goals.

For the most part, the policy maker’s one-stop solution for increasing the level of education in Pakistan has focused on raising the enrollment rates in primary schools. While this approach emphasized more on the quantity of education being provided, it has done little to cater to the quality and expense of the education itself. This is reflected in the learning levels of public schools in Pakistan, which are astonishingly low as student’s performance in academics is hugely underwhelming, compared to the acceptable standard. This shortcoming in the public education is mainly attributed to the dearth of incentives for public sector teachers. Which translates into low teaching effort, since any chance at salary increment and promotion is directly related to seniority and experience and not the teacher’s actual performance.

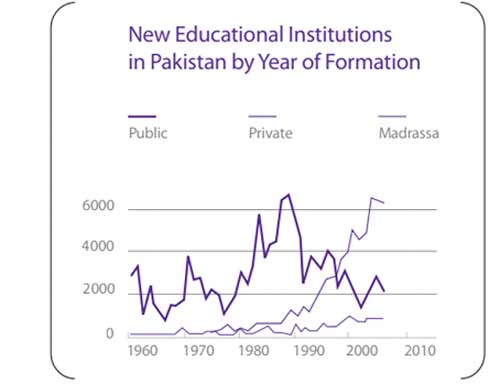

In view of these prevalent conditions of the public sector education, Pakistan witnessed a sudden boom in low-fee private education institutions in early 2000’s, which outnumbered state-run schools in both quantity and quality. With ample availability of low-cost teachers in rural areas due to lack of other job opportunities, these schools quickly expanded in the region and provided multiple schooling options for the 63% of the population which resides in the rural setting. Despite the private sector teachers being underpaid and under-experienced compared to their public sector counterparts, the learning levels of students in private schools has been much better. This is mostly due to effective teaching pedagogy, curriculum design and proper oversight which gives private schools an edge over public sector ones.

In the Human Rights Watch Report titled “Shall I Feed My Daughter, Or Educate Her?”: Barriers to Girls’ Education in Pakistan”, the Pakistani government’s inability to adequately educate the girls also surfaced. Liesl Gerntholtz, the Women’s Rights Director at Human Rights Watch commented “The Pakistan government’s failure to educate children is having a devastating impact on millions of girls”. The report stated that the majority of the 22.5 million children that are out of school are girls, who are simply barred from attaining education.

However, many of the barriers to girl’s education lie within the education system of the country itself. The State takes on a lasses-faire approach towards providing education in the country. And instead relies on private sector education and Madrassahs to bridge the gaps in education provision. Thus the girls are deprived of a decent education in the process. The government’s inadequate investment in schools is another main culprit for the number of girls that remain out of school. As girls finish primary school, secondary schools are not as widespread and their access to the next grade is hindered. Furthermore, while the Constitution of Pakistan claims that primary schooling be free of charge, it is not actually the case. Hence, most parents with constrained resources opt to educate their sons over their daughters. As a result, once girls are dropped out of schools, there is no compulsion by the state to re-admit the girls into school. Therefore, a chance once lost is lost forever.

Towards the end of 2019, Covid-19, which emerged in the wet markets of Wuhan, quickly took the world by storm. It forced the entire world into lockdown, and resulted in a major humanitarian and economic catastrophe, ultimately affecting the Education Sector as well. This compelled Pakistan to take swift notice of the virus and announce country-wide closure of educational institutes from beginning of February 2020. It wasn’t for another six months that educational institutions were reopened with strict SOPs in place, only to be shut down again amidst the second wave of the virus. And so due to these conditions, the education sector in Pakistan faced a devastating loss of learning. The virus not only exposed the cracks in the country’s education system, but it also further amplified them.

According to a report published by the World Bank “Learning Losses in Pakistan Due To Covid-19 School Closures: A Technical Note on Simulation Results”, it was predicted that a loss of livelihood due to Covid-19 could translate into a severe case of children dropping out of schools. The study estimated an additional 930,000 children that are expected to drop out of the fold of education, and thus increasing out-of-school percentage by 4.2 percent.

Similarly, the report also mentioned that the learning levels in schools could drop to anywhere between 0.3 and 0.8 years of learning. Therefore, an average student now only attains an education level of 5 years due to poor quality of education, despite going to school for 9 years. Furthermore, in wake of covid-19, the share of children who are unable to read basic texts by age 10, represented by “Learning Poverty” are further expected to go up 4 percent from 75 to 79 percent. As schools were shut down across the country, many of them were also unable to transition into online mode of learning. This was because the state failed to provide internet access to remote regions of the country. Hence, Covid-19 proved to be a huge setback for the education sector of Pakistan.

To conclude, while significant steps have been taken to strengthen the education sector of Pakistan, such as the unanimous passing of the Article 25-A of the Constitution of Pakistan and the dedication towards achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) to provide quality and equitable education; there still remains a gap between policy formation and its implementation. Despite the education policies of Pakistan focusing on science and technology, nationalizing private education institutions, increasing the number of student enrollment and improving their access to higher education, it still failed to improve in the education indicator of the HDI in the past decade. In view of this, Pakistan needs to rethink its education policies and fill gaps that currently exist between what is decided and what is implemented.

Courtesy: Published at Modern Diplomacy EU on January 23, 2023